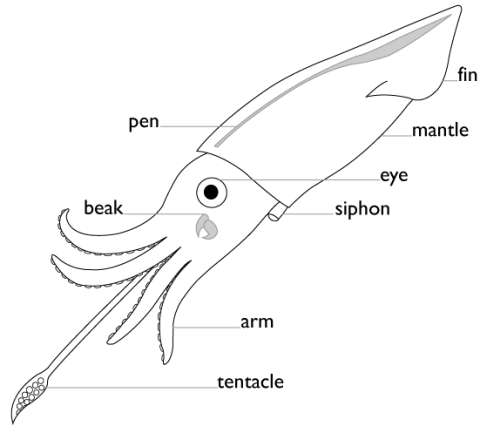

The name cephalopod means “head foot,” and these animals are so named because their “feet,” which we usually call arms or tentacles, grow directly from their head. You could approximate this body type if you removed all four of your limbs from your trunk and re-attached them in a circle around your mouth. It’s a bit disturbing, but the cephalopod body makes evolutionary sense. Early cephalopods all lived inside shells like snails, and it was advantageous to keep their soft organs, like gills and stomach, packed away inside the protective shell. Meanwhile, the head with its eyes and mouth and the grasping arms all needed to stick out of the shell’s opening to do their jobs. Thus, the origin of the head-foots

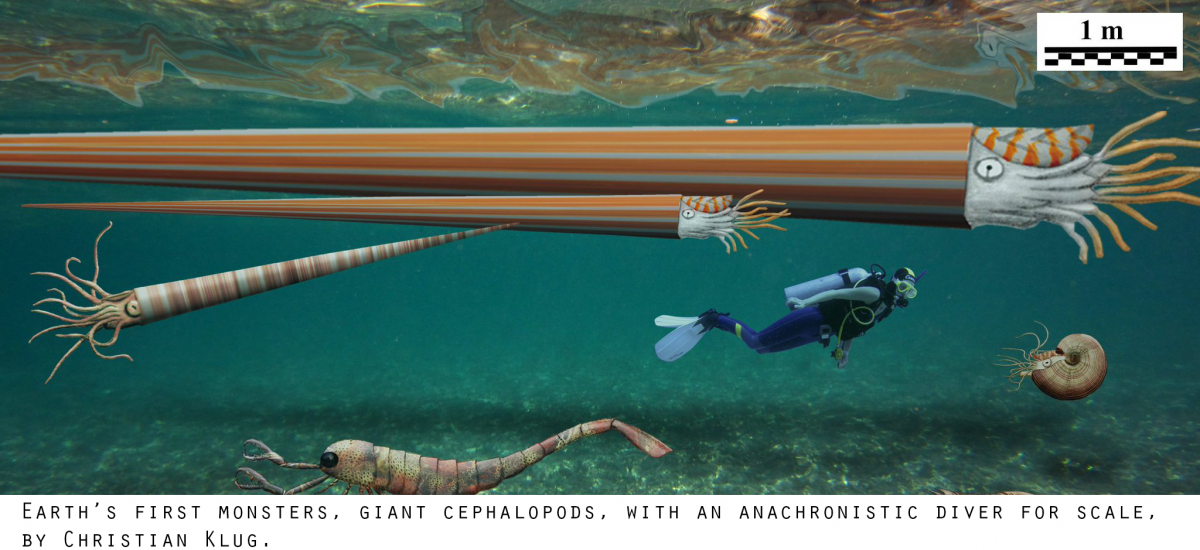

From one point of view, that was the heyday of the cephalopods and it’s been downhill ever since. As vertebrates evolved—first fish, then reptiles and eventually mammals—cephalopods would never again be the largest animals on the planet, nor the dominant predators.

Evolutionary pressure from fast-swimming, shell-crunching vertebrates drove cephalopods to evolve tightly coiled shells and eventually to lose the shell altogether, giving us today’s streamlined squid and amorphous octopuses.

From another perspective, cephalopods are still wildly successful, and we may even be in the midst of their renaissance. The head-foots have been around nearly twice as long as the dinosaurs, surviving all five of the planet’s previous mass extinctions. Many cephalopod species seem well poised to adapt and flourish in today’s changing oceans. And they’re gaining popularity with Earth’s current dominant species, as people sport t-shirts proclaiming “Welcome Squid Overlords” and join groups like OctoNation, “The Largest Octopus Fan Club.” With all due respect to birds and their kin, I like to think of cephalopods as “the new dinosaurs.”

Bio: Danna Staaf is a freelance science writer with a PhD in marine biology. Her book Squid Empire: The Rise and Fall of the Cephalopods chronicles the 500-million-year evolutionary journey of cephalopods from masters of the primordial sea to calamari on your dinner plate.