There’s a whole universe of life in the ocean we can’t see – thousands of tiny animals make up the zooplankton. Animals we commonly see in tidepools, and sometimes on our plates, begin their lives drifting in plankton. Planktonic larval stage in life gives species a way to disperse. The larvae develop while adrift at sea, often going through many stages before reaching adult body form.

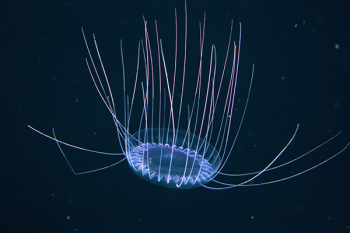

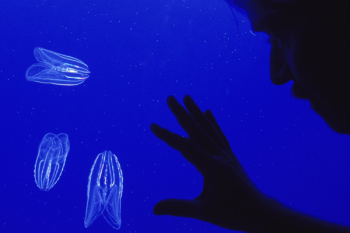

Looking like something out of a Dr. Seuss book, the larvae often don’t resemble their adult form. They have spines and feathery projections that keeps them afloat. Larvae are usually transparent so predators have difficulty time seeing them. Some species spend only a few minutes as floating larvae, others can live in the plankton for a year.

When larvae are ready to become adults, they somehow find their way to the shore by riding inshore currents. They then quit swimming and go through a metamorphosis, often as elaborate as a caterpillar changing into a butterfly. How a tiny drifting larva can find the right place to settle is an amazing feat, which scientists are just beginning to understand.

The animal groups with larvae in the plankton include, sponges, crabs, sea stars, snails, worms, and fishes.

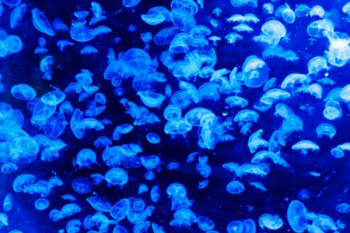

These tiny larvae are not the only ones out there floating around in the plankton. There are lots of different plants called phytoplankton and animals called zooplankton that spend their entire lives in the open ocean. All these organisms – phytoplankton, zooplankton and larval forms are key to the ecology of the oceans. They support the oceanic food web and cycle elements in the sea.

The phytoplankton, are the base of the oceanic food web. Zooplankton eat the phytoplankton; numerous small fish and invertebrates feed on zooplankton; bigger fish feed on the smaller ones; even bigger fish, sea birds, sea turtles, and marine mammals are at the top of the food web. Those tiny drifters support the entire oceanic food web.

Zooplankton and phytoplankton drive oceanic carbon and nutrient cycles. Zooplankton feed in surface waters and produce sinking poop pellets that transport organic matter to deeper water. And many of the larger ones carry organic matter to depth because they migrate daily from the surface to mid-water. Scientists studying carbon in the ocean try to measure how these animals contribute to the carbon cycle and how the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

More Resources:

This Stanford site shows many invertebrate larval forms and their adult forms.

This site, “Virtual Urchin” offers lessons about sea urchin development and how climate change is affecting sea urchins.

Here's a great video bout plankton and a lesson plan.

This article addresses how hard it can be to identify larvae to the species level and how genetics can help.

Scientists are trying to understand how larvae manage to settle in their right habitat by using robots.