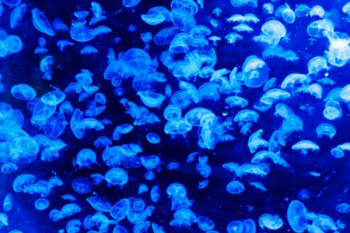

In places around the world there are so many jellies in the sea that fishing nets and nuclear reactors become clogged with gelatinous blobs that also cover beaches and freak out tourists.

These are signs of jelly blooms – when huge numbers of jellies, often in the millions, appear seemingly out of nowhere. There’s a perception that there are more jellies and jelly blooms in the ocean now. But, is that true?

The Jellyfish Blooms Working Group tried to answer this question. Looking at data from around the world, scientists wanted to know if there are more jellies, and if so, what’s causing the increase? This project is called JEDI, Jellyfish Database Initiative. Their results indicate that there are natural ups and downs of jelly populations. And that much more data is needed to understand if there is actually an increase in jellies ocean-wide.

Because jellies are important members of oceanic food webs, blooms can impact entire pelagic food webs. Food availability generally drives and shapes the booms and busts of jellyfish blooms. Jellies prey on a broad spectrum of zooplankton species and fish larvae, so a bloom ripples through the entire food web. Also, dead jellies that fall to the bottom contribute to the deep-sea food chain.

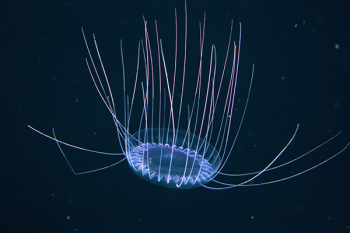

Scientists think that a combination of environmental triggers, such as increased nutrients flowing from land, overfishing, the increase of human-made hard surfaces, and climate change can promote jelly blooms. Jellyfish have a complex life-cycle with both bottom-dwelling polyps and open water medusae. Fertilized eggs released by adult jellies settle to the bottom and become tiny polyps. The polyps then release tiny jellies, called ephyrae, that grow into adult jellies. Some scientists think that a warming ocean and increased nutrient runoff into the ocean from human activities means more polyps to release more ephyrae, which then become a massive bloom of adult jellies.

Climate change

The ocean is absorbing almost all the heat from the atmosphere in the climate crisis. Some research shows that increased water temperature can boost jelly blooms. Warmer ocean water in the winter can increase the reproductive rate of temperate jellyfish populations, particularly in regions with limited food availability.

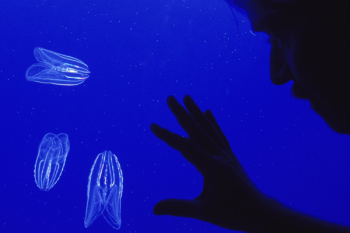

You can help: be a citizen scientist and report jelly sightings to help fill in the research gaps.