Crabs migrate to mate

Birds do it, amphibians do it, mammals do it, and so do marine arthropods. They all migrate. Most marine arthropods migrate for mating, others migrate for feeding.

Horseshoe crabs

Each spring, up and down the east coast, horseshoe crabs crawl out of the ocean under a full or new moon to lay their eggs on the beach. In Delaware Bay hundreds of thousands of horseshoe crabs leave the depths to spawn on Delaware Bay’s sandy beaches – it’s the largest spawning area in the world for the horseshoe crab.

One observer describes the mass spawning this way: “Male horseshoe crabs arrive just ahead of the females, forming a shifting boulder field that females must plow their way through to reach suitable nesting sites along the high-tide line. As they make their way, the smaller but determined males swarm the females, shoving and sliding, until one male can successfully grab onto her shell with his front legs and pull himself aboard.” Other males follow, jostling for a good position by the female. Once the female reaches the wet sand, she digs a shallow nest and lays a clutch of several million eggs, which are immediately fertilized by the surrounding males.

The millions of eggs cover Delaware Bay’s beaches. And those eggs provide a critical feast for migrating shore birds, the red knot. Red knots feast on the crab eggs to fuel their 4,000 mile journey from South America to the Arctic.

Watch our video about horseshoe crabs

Alaskan red king crab

Alaska king crabs—both red and blue—live from the intertidal zone to 600 feet or more. In the cold, deep water, these crabs form large aggregations called pods that can be several feet high and consist of thousands of crabs. Scientists think podding is defense against predators. Adult crabs tend to segregate by sex off the mating-molting grounds.

But adults of both sexes make annual migrations from the deep in late winter to their shallow mating grounds. Adult male red king crabs have been known to migrate up to 100 miles round-trip annually, moving at times as fast as a mile per day. They molt and mate before they start back to offshore, deeper waters. By spring the females’ embryos hatch to start their lives in the plankton before settling and starting the cycle again.

Giant Spider crabs

Giant spider crabs live on the seafloor off the coasts of Japan and Australia from 660 to 1800 feet (200-550 meters) deep. The body of the Japanese spider crab is 12 inches (30 centimeters) across, but the legs can span up to 12 feet (3.8 meters) long. It’s the largest crustacean.

These denizens of the deep only come near the surface to mate and reproduce. Between January and April giant spider crabs migrate to the shallower waters—about 160 feet (50 meters) deep to mate and spawn. Female spider crabs can lay up to 1.5 million eggs in a season, but only a few survive.

Hermit crab

They migrate by the thousands, like lots of animals do. But these are small migrators: hermit crabs. They live on land throughout the Caribbean, but every year in late summer they march to the coast at night. The crabs spend four days to a week walking down from the forested hillsides to the ocean. Scientists think they mate en route. Or in some species the mating takes place in the woods and only females migrate. Once close to shore females congregate, leave their shells and enter the water to spawn. When they're done, they return to shore and crawl into any available shell. Then the adults head to the hills.

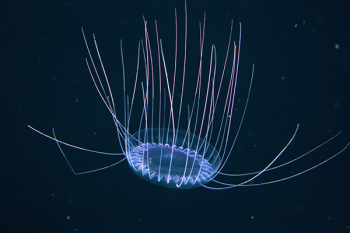

Copepods and Krill

Copepods and krill are small crustaceans that are abundant in the zooplankton. They are part of the earth’s largest migration, the daily vertical migration, where animals commute daily from the depths of the ocean to its surface. This migration occurs from the tropics to the poles. They migrate towards the surface at night to graze on phytoplankton and zooplankton, and return to the deep during the day to reduce the risk of being spotted by visually-hunting predators. Copepods are amazing swimmers: they can travel 295 feet (90 meters) in an hour—the equivalent of a human swimming 50 miles per hour.

Krill are important because they convert microscopic phytoplankton into a food source for numerous other species including fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Watch this video about the migration.