I have always wanted to see flocks of migrating shorebirds on their way to their breeding grounds in Alaska. The Copper River Delta is the best place to see this spectacle, so I went there with my sister and two naturalists who have studied migratory shorebirds for decades. Nils Warnock, head of Audubon Alaska, studies shorebirds both by observing them and tracking them by banding their legs and gluing tiny transmitters to the feathers on their backs. Stan Senner is Audubon’s Pacific Flyway Director developing conservation strategies and policies to conserve habitat for shorebirds along the flyway.

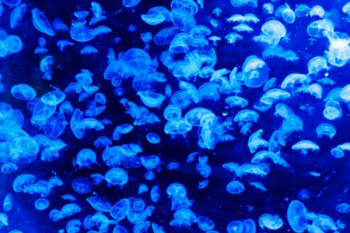

The first evening was beautiful and then it rained, sleeted or snowed the rest of the three days, which really wasn’t so disappointing. Usually bad weather brings the birds down to rest and feed on the mudflats. But this time there were only thousands of shorebirds, not millions, at least where we were. Most were western sandpipers in their stunning breeding plumage, constantly feeding at the surface of the mud and among the sedges. We did see a merlin – a small falcon – repeatedly swoop down over the birds, startling them into their swirling dance as they escaped. Then all of a sudden there was the merlin with a shorebird in its talons.

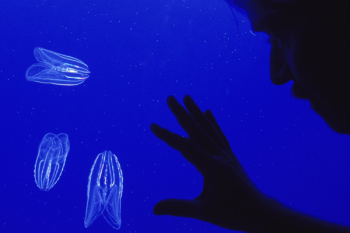

The western sandpipers are the most abundant shorebird in western North America. It is amazing that these small birds (0.8-1.2 ounces) fly thousands of miles to Alaska just so their young can gorge on the abundance of insects. The entire population of western sandpipers, as many as 6,500,000 individuals, passes through the Copper River Delta each spring. The birds spend the winter along the west coast from Washington to Peru. When migrating north, many rest at several stopover sites for a day or two just long enough to fuel up. This series of stopover sites from Peru to Alaska is called the Pacific Flyway. The birds require energy reserves that they get at these stopovers, essential for their migration. They feed on tiny macoma clams and other invertebrates in the mud, and also skim the surface for a film of diatoms, microbes, and detritus. Most travel 356 to 1000 kilometers/day (227-620 miles/day), but a few can fly as far as 2100 kilometers (1300 miles) in just two days.

Check out this map of their migrations.

Protecting Their Home Away from Home

It’s so important to conserve habitats that are essential to these shorebirds. Nils says about the decline in coastal habitats, “These declines represent the No. 1 conservation crisis facing birds in the world today. Climate change, coastal development, the destruction of wetlands and hunting are all causing a decline in shorebirds. Because these birds depend for their survival, as we do, on the shorelines of oceans, estuaries, rivers, lakes, lagoons and marshes, their decline points to a systemic crisis that demands our attention, for our own good.”

Birds from all over North and South America breed in the Arctic, following four different North American flyways. Nils says, “…. at Audubon Alaska we emphasize this all the time. The Arctic holds breeding grounds for all four North American flyways; birds connect Alaska to every other state in the country, and to every other continent on the planet. That just shows you how interconnected we all are.

And I sure felt that connection when I saw in the Copper River mudflats, those same tiny sandpipers I watch probing the mud at Elkhorn Slough in Central California, near my home.

Here is the website of the incredible photographer who shot the images.

More about the western sandpiper.

Learn more about shorebirds.