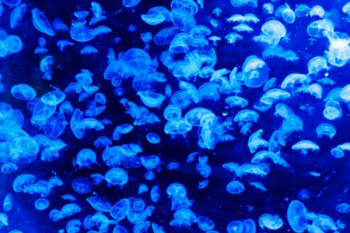

The Octopus Garden, as scientists named the site, is located at the base of the Davidson Seamount, in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Scientists have seen thousands of octopuses there— the largest congregation of octopuses discovered to date.

This unique behavior raised a lot of questions for the scientists: why do the female octopuses congregate here?

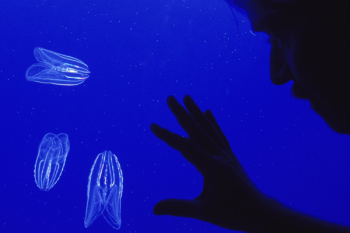

Deep sea octopuses normally breed for several years because the cold water slows the development of the eggs. Since the temperature at the octopus garden is around 1.6 degrees C (35 F), scientists thought this species of octopus, Muusoctopus robustus, would breed for a very long time. But when researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) measured the water directly under the eggs, they found it was 10 degrees C. The octopuses were nesting in warm water seeping from the rocks! The females were tucked into nooks between the rocks, nestled around their egg clusters in a brooding posture, their eight arms facing out to cover their bodies and the eggs underneath.

Do the eggs develop more quickly at this higher temperature? In February 2022 MBARI scientists reported that warmer water does speed up development of the octopus embryos. In the deep, cold waters of the seamount, embryos would be slow to develop. But in the warmer water, scientists calculated that the octo-moms brooded for only about a year and a half, faster than predicted for that part of the deep sea. It makes evolutionary sense to nest where development time is shortened: fewer eggs are likely to be eaten by predators.

Most female octopuses, no matter where they live, brood their one set of eggs until tiny octopuses emerge. Then the female dies. But scientists don’t know much about brooding behavior in deep sea octopuses. MBARI scientists did track one deep sea octopus over time and found that she protected her eggs for four years, longer than any other animal known to science.

Watch a video of the Octopus Garden