Why Being Green Reduces Stress

Life can be stressful for anemones. Fortunately, the green microalgal symbionts in some anemone tissues provide them with nutrition and antioxidants that help them cope with stressors.

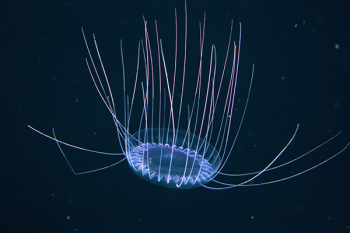

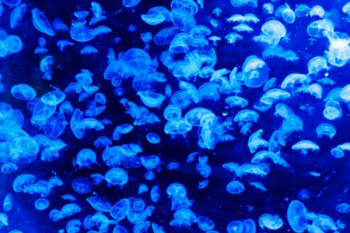

Sea anemones, Cnidarians that sometimes look like flowers, can be tiny or meter-sized, ranging from the poles to the tropics. There are no freshwater anemones. They are found from shallow shores to more than 32,000 feet below sea level. Anemones live on coral reefs and in the rocky intertidal, exposed to air when the tide is out. When anemones are closed, people may think they’re not alive. They most certainly are. Thank you for NOT stepping on them.

On the rocky shores of the west coast, there are three species of Anthopleura anemones: the aggregating anemone (Anthopleura elegantissima), the giant green anemone (Anthopleura xanthogrammica) and the sunburst anemone (Anthopleura sola). All of these are green of various shades; some are even neon green. All have symbionts and they’re the only anemones on the coast that have symbionts that are green. The microalgal symbionts living in their tissues provide the animals with nutrition in addition to what they get from the prey they catch.

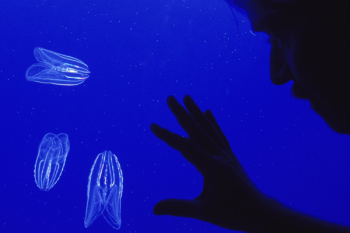

But it’s not the symbionts that give the anemones their color. The green is from a protein called Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). It’s the same family of proteins as the well-known jellyfish GFP used in medical research. These GFPs revolutionized cell biology and led to the new field of in vivo cell biology. Researchers attach the protein to cells as a fluorescent tag so they can study their behavior in real-time to better understand cellular functions. The GFPs can also act as a marker helping scientists study gene expression.

For a long time, scientists didn’t know why cnidarians, in general, and green anemones in particular, had these proteins. A recent study shows the proteins don’t just provide the brilliant green color, they act as anti-oxidants which protects their cells from stress. All of these anemones live in the intertidal where the animals have to deal with a variety of stressors: drying out, UV radiation and temperature and salinity changes daily as well as seasonally. Nate Clarke says, “This dual role of fluorescent proteins — as agents of both coloration and cellular defense — highlights the sophisticated ways marine life adapts to the challenges of their environments.”