The sunflower star is one of approximately 2000 sea star species worldwide. It’s the largest sea star with the most arms. Those arms have given it the common name: sunflower. Sunflower stars are voracious subtidal predators, feeding on bivalves, snails, urchins, other sea stars, sea cucumbers, sand dollars, and crabs. And it will also scavenge dead animals. Sunflower stars can move very fast, for a sea star. Watch this Shape of Life video below.

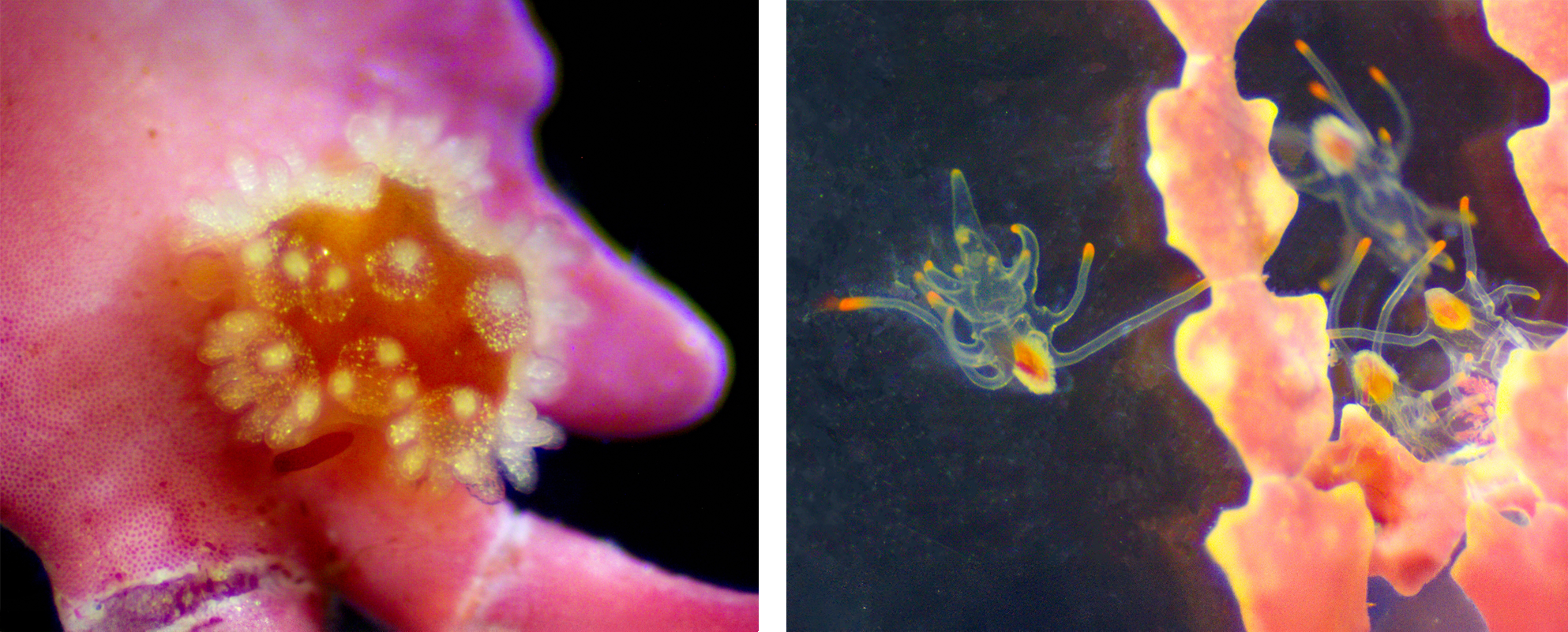

Sunflower stars are broadcast spawners: the sea stars release eggs and sperm into the ocean. The fertilized eggs develop into bilateral larvae that live in the plankton for about 10 weeks.

Once the larvae touch the bottom, the sea star consumes the larval body as it metamorphoses into a juvenile with five arms. As the juvenile matures, it grows more arms clockwise, starting from the two rays closest to the sea star’s center. It adds two at a time, bilaterally. Adults can have as many as 24.

There is little known about the species’ basic life history, including growth and survival among life stages, generation time, and adult densities needed for spawning, and successful population growth. Scientists are researching all of these questions as part of the recovery of the species.

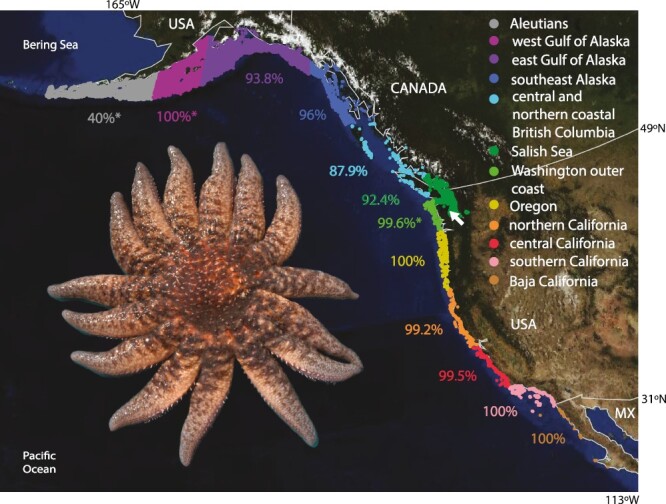

This large sea star has been in the news a lot lately (see our Blog and Featured Scientist) because it has disappeared from most of its range along the west coast, as shown in the map below because of sea star wasting disease.

“The sunflower sea star, Pycnopodia helianthoides, historically occurred across ~6,000 km of coastline from Alaska, United States, to Baja California, Mexico (MX), but exceptional mortality during an outbreak of SSWD beginning in 2013 halved its range, restricting the species to Alaska, British Columbia, and northern Washington. Colored regions show estimated percent declines in sunflower sea star population density due to SSW between 2013 and 2017 (inset) Photograph of P. helianthoides from the Salish Sea, courtesy of Taylor Frierson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Scientists didn’t know a lot about the sunflower stars’ genetics until the disease outbreak. What they found is that coastal populations from Monterey up to Juan de Fuca are pretty uniform until you get to the fjords in British Columbia. Alaskan populations are separate. Genetic knowledge is important for understanding the impacts of disease and also for informing captive breeding and rearing efforts, as well as guiding where the captive bred sunflower stars should be returned to the wild.

Sunflower Stars and Kelp Forests

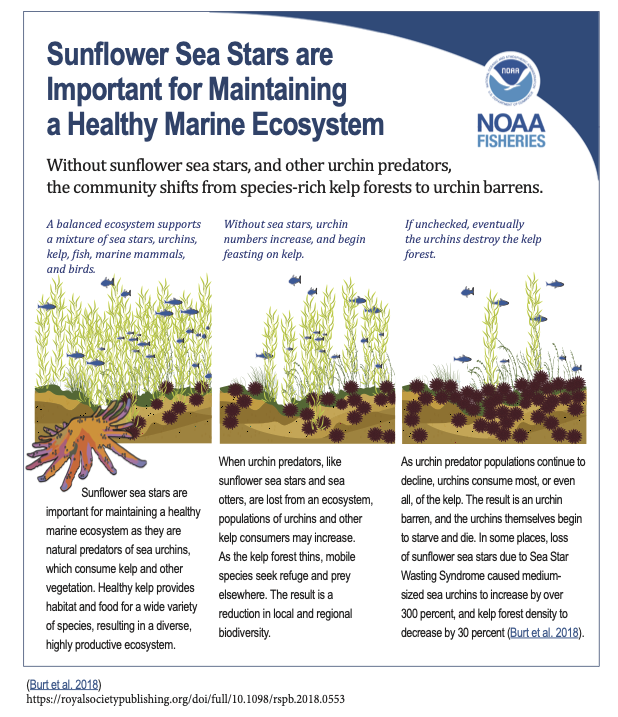

Before SSWD wiped out virtually all sunflower stars, they served as keystone predators, protecting kelp forests from overgrazing by urchins, thus keeping kelp forests rich in biodiversity. Since then, many kelp forests have become sea urchin barrens where kelp is absent or minimal and sea urchins are everywhere. So, one of the goals of the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group is to develop methods to grow sunflower stars at the scale needed for kelp forest recovery. (See Blog)

Sea stars connect to people in ways we might not appreciate: they are gatekeepers of ecosystem health and resilience. They are both grazers and predators that have been around for over 540 million years. The loss of sunflower star populations up and down the coast has devasted kelp forest ecosystems. Sometimes you have to lose something to understand its benefits. As the song lyrics say “You don’t know what you’ve got “til it’s gone.”