Senior Education and Research Specialist, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Diving Into an Amazing Future

Despite having “abominable GPA and GRE scores”, George found his way to discovering a new species of ctenophore and a prolific life as a scientist. “I once looked over my notes from undergraduate school and noticed a pattern of vertical lines throughout them. They were my pen marks from where I fell asleep while studying!” laughed George.

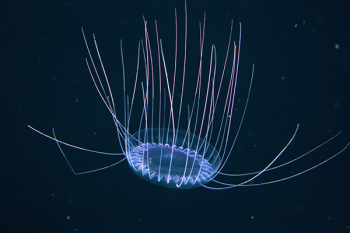

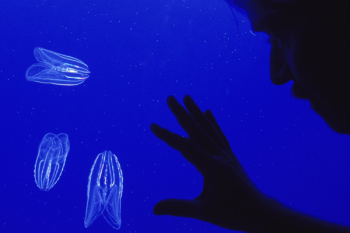

It was through George’s love of the ocean, and diving, that he became a world renowned expert on comb jellies- a little-known group of animals.

George studies deep sea comb and other jellies at MBARI. They’re ideal animals to study with Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV’s) like ‘Doc Ricketts’ because they can’t hear or see the ROV. The deep sea is an unexplored aspect of the ocean, so most of the jellies that George and other scientists find are new species. George is fascinated by how animals survive in the water column with no place to hide. Many deep-sea animals have unique adaptations like being transparent, or red, or having a red gut to mask their organs.

One of the advantages of MBARI expeditions is their decades of exploration and the Deep Sea Guide, a database that catalogues all images and videos of their discoveries. Scientists refer to the database as they dive, calling up images and data relevant to their mission, in real-time, while also contributing newly discovered data in the process.

Curious George

George wears many hats at MBARI. Research is 20%; 80% is outreach. When wearing his “Outreach Hat” he works with the MontereyBay Aquarium. He’s currently working with the Monterey Bay Aquarium in collecting animals for new deep sea exhibits.

Diving into the deep, dark ocean armed with only a flashlight, 3 miles offshore and 6000 feet of ocean- George ‘blackwater dives’ in Hawaii to collect animals that come to the surface at night. YIKES!

George also runs the intern program at MBARI. “I see my role as giving aspiring researchers a very real-life taste for what it’s like to be a researcher—with all the tedious tasks and glory involved.”

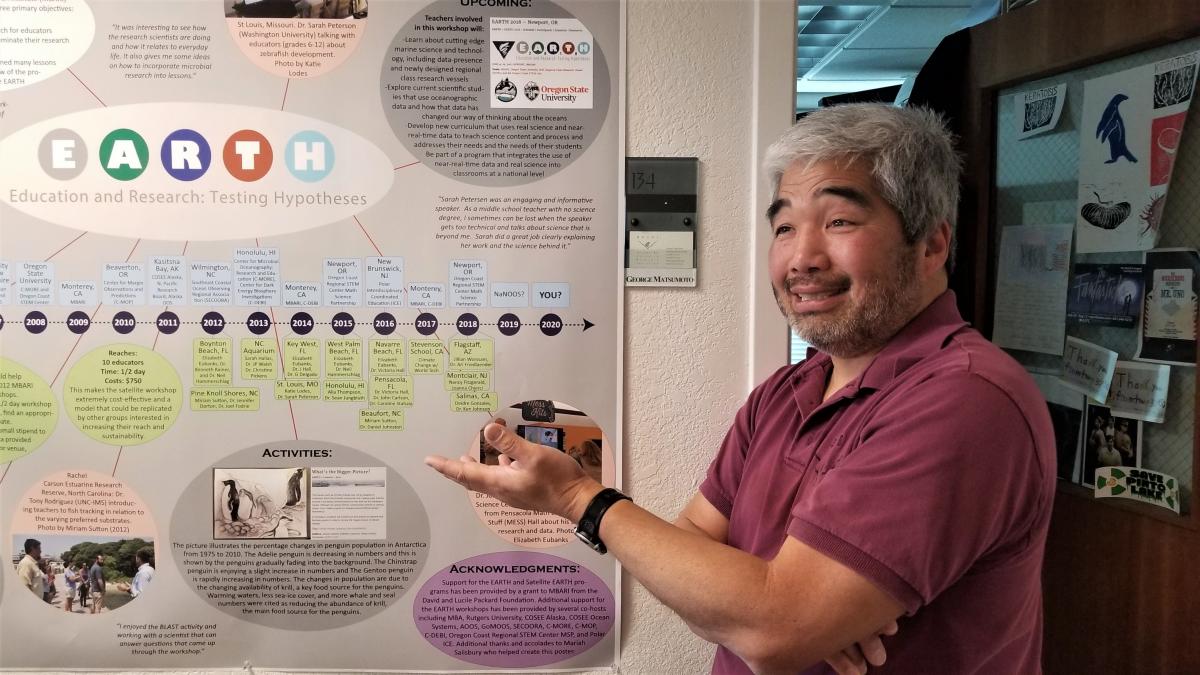

George also directs teacher professional development called Education and Research: Testing Hypotheses (EARTH). Working together, educators and researchers gather real data resulting in lesson plans they share among one another and their students.

Running the “Adopt-A -Float” program is another hat that George wears. The floats are at 1000 to 2000 meters below the surface. Teachers and their students adopt, follow and download data from their float. This gives the students ownership of the data.

Oh, George also teaches environmental science for non-majors at Monterey Peninsula College. With his engaging personality, George inspires non-science-y students to cultivate an appreciation for both the natural world and critical thinking in how they approach the world.

Jelly Blooms and Climate Crisis

Oceans are warming with climate change and this could impact jellies, but “we just don’t have enough longitudinal data to make a definite conclusion,” adds George. Jellies have calcium carbonate balance organs, so may have trouble surviving a more acidic ocean. Additionally, jellies need something to eat, like crustaceans and fishes, and warming and an acidifying ocean negatively impacts the food web.

At Shape of Life, we know our materials are particularly relevant to middle school science teachers. When we asked George why middle school science is so interesting to him, he responded: “Middle school STEM is probably the last time you learn about science within the context of the whole world. As you proceed in learning science, it becomes so much more specialized. Science is the whole picture of how we are connected.”