The Curious Path to Conservation Policy

It’s a really good thing (for all of us!), that Kelly ignored the discouraging messages she received in high school.

“I didn’t plan on becoming a scientist. In fact, in high school I was told I wasn’t smart enough to pursue science. Worse, I believed it. That was before I made the connection between science and how much I love being in nature.”

Kelly’s Unexpected Path

When Kelly went to college at Middlebury where she intended to study international politics. Part of the deal was Kelly had to fulfill a science requirement for her major and she selected environmental geology. Despite being discouraged from studying science, Kelly found she did indeed have an aptitude for science. She especially loved that her geology class was all outdoors. She immediately switched to a major in geology.

The Greenland ice core data records were published while Kelly was an undergraduate. The data from those records revealed to Kelly the connection between climate change and human impact. Kelly eventually received her M.S. in Oceanography and then a Ph.D. from Boston University in Earth Science. She had always wanted to go to Antarctica for research.

And boy, did she go! Kelly spent four separate two-month stints collecting and studying sediment cores that record climate history.

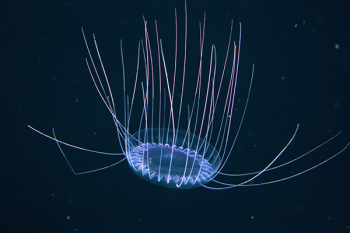

Kelly worked on a range of research that included marine geology, geophysics, magnetics, atmospheric chemistry, geochemistry, and paleoceanography. She was part of the ocean science community that travels the world on research vessels for months at a time.

Science & Policy Action

After her years of scientific training, Kelly took her multi-disciplinary experience into real world issues by helping policymakers. Kelly makes sure environmental policy decisions are informed by scientific realities. Because Kelly is gifted with a ‘right and left’ SUPER BRAIN, she’s able to

serve as a conduit between politicians and scientists – often analogous to blending oil and vinegar.

At first, Kelly did policy work in government as a political appointee under the Obama Administration – working for the Senate Energy Committee, the White House, and State and Interior Departments.

Kelly is now the first Director of Conservation Policy and Leadership at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life; Ocean Life Center at the New England Aquarium. One of Kelly’s projects involves the North Atlantic right whale, which the New England Aquarium has studied for 40 years. It’s an endangered species whose decline is hastened by ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear.

“This species lives its life on the highly industrialized east coast of the North American continent, bearing the scars that come with the activities humans conduct in their habitat," said Kelly.

Kelly believes many solutions are political. “We know nearly every individual whale. We know their family members. We know where they like to spend their summers. We know who’s been having babies,” said Kelly. “We also know which ones have been hit by ships, and which have been cut by propellers and been entangled in fishing gear. While some may survive these encounters, many do not.”

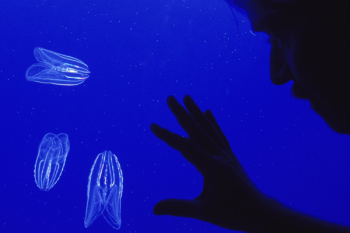

Kelly’s second project involves working on the global campaign to protect 30% of the land and sea by 2030. Research says setting aside special places is part of a tool kit that helps with climate change adaptation, removing the stressors of fishing and offshore oil and gas extraction to better build resilience for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

Scientists: Political Champions of the Environment

“I’ve noticed in the past three and a half years that scientists are recognizing the need to speak up,” said Kelly. “Their work is becoming more ‘cause-driven’. In this pandemic, it’s a cause for celebration to see the world rallying around science and its rigorous pursuit of a solution to our tragic health crisis. Science is a great equalizer in terms of showing the world how to cooperate,” Kelly thoughtfully added.

Nutral Curiosity

“Curiosity and a drive to understand is the heartbeat of a scientist,” said Kelly, “I think it’s very important that we instill a strong sense of curiosity in young students.”

We’re certainly all the better for Kelly’s sense of wonder and curiosity. We can all be grateful that her desire to study outdoors overruled the naysayers of her aptitude for science. We suspect the world will benefit from Kelly’s aptitude for many years to come.

Read more about the policy work at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life: Transforming Science into Action