Dr. Jessica Ware is an Associate Curator in the Division of Invertebrate Zoology and Associate Curator and Principal Investigator, Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History.

Jessica Ware credits her grandparents for instilling in her a love of nature and interest in science. She grew up in Toronto, but spent time outdoors in nature in northern Ontario, picking berries and exploring the woods with her grandparents, who encouraged curiosity. She saw her first dragonflies, (her passion), on the lakes there.

Jessica studied mostly invertebrate zoology and entomology as an undergraduate, and decided to pursue a PhD in Entomology from Rutgers University where she focused on the evolution of Dictyoptera (termites, cockroaches and mantids) and Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies).

While spending time with her grandparents, Jessica sharef the joy of watching creatures in the natural world. It wasn't until grad school that Jessica learned that observing animal behavior was science. Dr. Michael May, her PhD advisor, was a behaviorist and encouraged students to study (observe) behavior.

Dragonflies

Earlier in her education Jessica heard that “if you are not doing math, you’re not doing science.” Later she learned that wasn't true—"we can do all sort of things and be a scientist, even without math!” Dr. May, encouraged Jessica to apply what she had learned in genetics to understand the evolution of dragonfly families as nobody had done molecular work on dragonflies. She focused on the evolution of a super family with 1500 species. Termites

For her post-doctoral research at the American Museum of Natural History, Jessica combined her interest in behavior with evolution by studying the evolution of the social behavior of termites. The evolution of termite social behavior is associated with diet and their need to colonize their gut microbiome. To do this the termites need to be near other termites with the same microbiome, so their diet drives their social evolution.

Dragonflies & Termites

Currently, Jessica studies the reproductive, social and flight behaviors of those two groups of insects; dragonflies and termites. She has looked at both the morphology and behavior of dragonflies, which have sophisticated mating behavior. For example, males displace previous males’ sperm. Female dragonflies deposit eggs in water or on aquatic plants. Some protect their eggs, which makes them vulnerable to attack and so restrains the number of eggs laid.

Migrating Dragonflies

Dragonflies migrate, an amazing thing to think about. How do they do it? Like monarch butterflies, the migration is multi-generational. Jessica studies flight behavior and the migration of dragonflies using genetics. Gene flow tells you the extent of migrations. Jessica has found long migrations in a skimmer dragonfly with both individuals and swarms dispersing thousands of kilometers over land and oceans.

The energetics of long-distance migration and how much fat dragonflies store is a keen interest to Jessica. Since they cross vast stretches of open ocean, they store fat that is not used until they reach land. To do this they put on fat right before taking off. And where do these delicate creatures store the fat? Like some of us, in their abdomens.

You have to wonder about their wings when thinking about dragonfly migration. Many wings are very aerodynamic, shaped like airplane wings: Jessica studies wing stiffness and shape. Some wings are stiffer, some more dense; and they need a balance between flexibility and stiffness to provide passive stability on long flights.

The Tree of Life

Jessica became interested in evolutionary trees. Jessica is studying the evolutionary history and relationships within groups of organisms. This is called phylogeny. Evolutionary trees are an essential tool for understanding relationships and the evolution of behavior. Jessica is working on a project that involves genetic sequencing of 1000 species of dragonflies. She is seeing the relationships between these species for the first time. She is also looking at the evolution of wings in cockroaches from wingless to very long wings.

Diversity is Healthy in Science, Entomology and LIFE!

Serving as president of the Worldwide Dragonfly Association., Jessica is very active in the Entomological Society of America and she says that Entomology is not as diverse as Jessica would like. In practice, entomologists of color often feel isolated. The Entomological Society of America wants to diversify through both recruitment and retention. Entomologists of color have become activists in helping to establish best practices.

There is progress as evident in the increasing numbers in ages below 30 where diversity is generally more commonplace. Jessica thinks diversity will come. Jessica says that entomology is a leader in diversity and inclusion with a strong vision and a community receptive to making changes. She is also a member of Black in Natural History Museums, an organization that wants to diversify natural history museums.

Exhibitions

Jessica was involved in the planning of the new Gilder Hall, at the American Museum of Natural History. She worked with other entomologists and exhibit designers to communicate the facts about insects, as well as their beauty. Inspiring wonder through the unique thing’s insects do as ecosystem engineers, and their importance in medicine and agriculture. Jessica and the other curators each had their own favorite insect they want to highlight. There are approximately 1.5 million described species; the exhibition includes 350 pinned insects from the collections. That involved some hard decision-making! Jessica had a lot of fun working on the exhibition and loved working with the team.

Disappearing Insects

Insects are in decline worldwide. Jessica is part of a grant called ENTOGEM that brings people together globally to look at the problem. She says they’re “trying to save humanity.” The grant coordinates the research of hundreds of scientists to look at all what’s impacting insects.

In relation to climate change, data suggests several things are leading to declines: global warming, droughts and extreme weather. Land-use changes, insecticides, pollution, and invasive species all have an additive negative impact on insect populations. The data suggests we don’t have much time left. It’s hard for Jessica to go home and forget these ominous results. We need masses of people to make changes to avoid the insect apocalypse. As a National Geographic article put it: “you’ll miss them when they’re gone.”

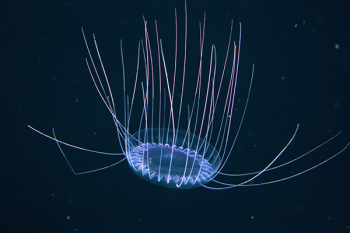

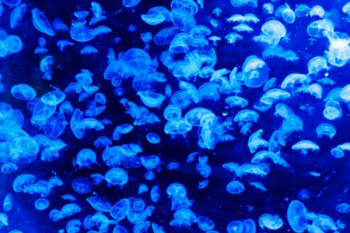

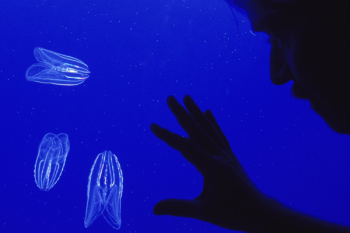

Jessica would like tell science students, “don’t limit yourself with preconceived notions of the science you want to do.” Jessica thought she wanted to be an oceanographer or marine biologist, but then took an invertebrate class and discovered insects. “Learn as much as you can, take a lot of science classes”, she says. Jessica believes there is no such thing as wasting time until you know for sure what course of science you want to pursue.

Check out Jessica on The Breakfast Club in this interview