Crissy was doing research on other octopus species in Indonesia when Sea Studios (Shape of Life was created by Sea Studios) filmed her with the venomous blue-ringed octopus – not for the faint of heart! Studying octopus’ behavior in the field was the basis of her PhD thesis at Berkeley and Post-doctoral studies at MBARI. Crissy’s passion for the ocean grew stronger, so she worked for several years in Raja Amput, Indonesia in marine conservation with Conservation International.

Biomimicry: octopus locomotion inspires robotics

After her conservation work, Crissy returned to MBARI. One of her projects is studying octopus biomechanics in the Bioinspiration Lab at MBARI with Kakani Katija. Octopuses move all eight arms to crawl on the seafloor and over rugged terrain. How does the animal process and control those movements? If you want to make a small soft robot, mimicking octopuses as a model is one approach. Watch this.

Octopuses can move using highly stereotyped behaviors and muscular joints. They can bend anywhere but, the researchers hypothesize that they don’t. They need some rigid body part that meets the seafloor. Crissy is testing that in the Bioinspiration Lab using footage of the pearl octopus (Musoctopus robustus) that lives in the deep sea. Maybe this knowledge will lead to more robots like this “octobot.”

Crissy loves being in the water with octopuses as they flow and shape shift. But this deep sea pearl octopus crawls out in the open so it’s one of the few octopuses that’s easy to see. It looks like a stick-figure octopus. It doesn’t have to worry about predators where they live. They are slow and simple; slow because its cold. They are the octopuses at the octopus garden.

Changing Ocean

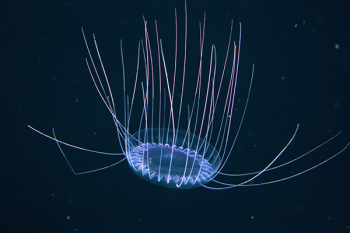

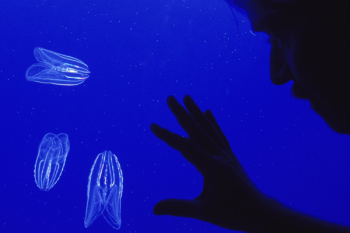

As a Senior Research Specialist, Crissy is also studying carbon sequestration and ecosystem change in the deep sea. The ocean is essential to our survival. Marine animals are key for taking up carbon from marine snow. Marine snow starts at the surface where phytoplankton fix carbon dioxide into organic matter. Some of that carbon sinks as marine snow—poop and dead organic matter—through the ocean depths, settling on the seafloor. There the carbon is stored away from the atmosphere. Fish poop is key is carbon sequestration: some poop slowly falls to the bottom and is taken up by other organisms, which then also poop. The poop reaches the bottom and stays there.

Using advanced imagery of marine snow, Crissy is trying to quantify when there’s a lot of marine snow and when not. Most of our winters off the California coast are characterized by infrequent, unpredictable weather events. Marine snow events are also like that, coming in pulses. These pulse events are very important to the carbon cycle, but they aren’t represented well in the models of the carbon cycle.

The lab is also trying to understand why there is marine snowfall. They see stuff on the bottom that contains carbon but can’t trace the source. So they are taking pictures of what’s sinking at different depths. This means having instruments in the water all the time. Crissy and her colleagues are working on a camera that will trigger another robot to analyze the contents of marine snow.

Endless discoveries

For budding scientists, Crissy would like to say that there are so many exciting discoveries out there and more scientists are needed. There is not a single way to become a scientist; most people working as a scientists have had different career paths. Her advice: do what excites you.

Science Friday interviewed Crissy about cephalopods and about a deep-sea rover.

Read more about Crissy when we profiled her work earlier.