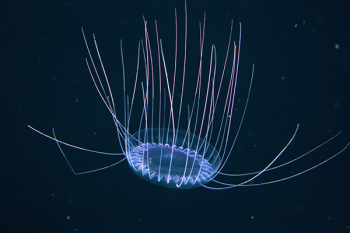

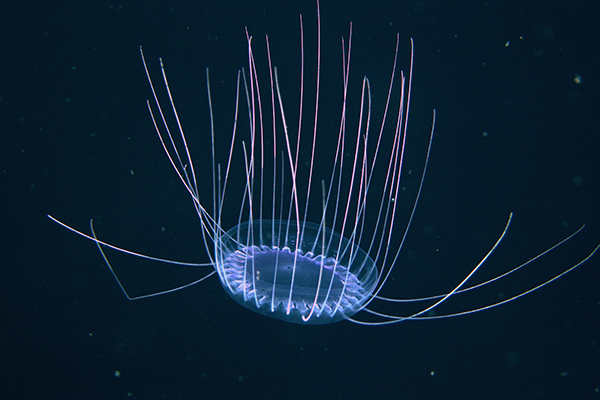

This jelly, named for its size and general shape, is a formidable predator where it lives—from the surface of the ocean to 6000 feet, but are most common in the deep sea.

Cruising the twilight zone, the large jelly (up to 20 cm, 7.9 inches size) chases down all kinds of gelatinous animals. We use the term “jelly” because these animals are Cnidarians, not fish at all.

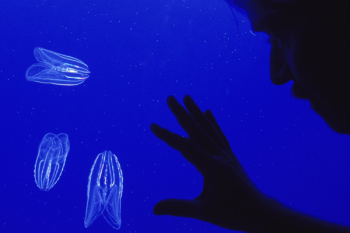

Unlike other jellies that trail their tentacles to capture prey as it passes by, Solmissus is an active hunter, swimming with its tentacles held out in front. This way it can sneak up on its prey without creating tell-tale water movement. The tentacles capture prey and then nematocysts — tiny harpoons—on the tentacles trap the prey. Watch this Shape of Life animation. Once the prey is stuck to the tentacles, they pass it along to its mouth.

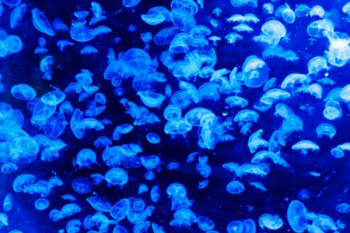

Scientists at MBARI, who use video to study deep-sea animals, have observed dinner plate jellies preying on 21 different specific animals including other jellies, siphonophores, comb jellies and more. They are a dominant predator of the deep sea worldwide.

Solmissus is a hydrozoan, a kind of jelly that’s different from a classic jelly. Hydrozoans have a polyp and medusa phase like other jellies; but the medusae are produced by buds instead of peeling off (strobilation). The dinner plate jelly that is so abundant in the deep sea is the medusa phase.

Like all animals in the midwater and the deep sea, human activities threaten the dinner plate jelly. Climate change is impacting midwater and deep-sea ecosystems worldwide and all of their inhabitants. And researchers are concerned that deep-sea mining will threaten the midwater food webs that Solmissus is part of.