Oh, The Places She Goes

Edie spent her time exploring all the new places. In Europe she decided she wanted to be an artist; in Egypt, an archeologist; in Asia, a humanitarian. When they reached Australia for a six month stay, Edie did what she always wanted to do- observe animals. She tracked wallabies, climbed trees to see koalas and observed penguins. On the way home the family stopped in Fiji and Edie got to see coral reefs. She decided then and there that she wanted to be a marine biologist.

Blind Luck

In college Edie took a class at Bimini Marine Lab confirming her career goal. As we’ve discovered with most scientists we interview, Edie’s path wasn’t a straight one. After a botched back surgery, she became temporarily blind, spending four months in the hospital. From this experience, Edie learned to prepare herself for the curve balls that life can throw.

One of Edie’s professors at Tufts inspired her when he talked about what it’s like to discover something no one has ever seen. She loved his physiology of behavior course and was fascinated by light and vision due to her temporary blindness. At one point, Edie considered electrical engineering but was told that “women don’t tinker” (she does!). So instead, Edie got a Master’s in Biochemistry and her PhD in a Neurobiology lab at the University of California Santa Barbara.

Seeing the Light!

In the lab Edie ended up working on bioluminescent dinoflagellates and became increasingly fascinated by how creatures make their own light. Her professor got funding for the newest, best spectrophotometer. Since Edie is a “gadget freak”, she became the expert in the lab. Edie was given the assignment of going to sea to measure light with the new instrument. And there she was: a seagoing marine biologist, living her dream.

The Deep Sea

Edie has spent hundreds of hours in the deep sea—mainly in submersibles, but also using a WASP suit—a one-person diving suit. She has lost count of how many hours she has spent in the deep sea. Is it spooky? There is always a risk being in a submersible and she has been afraid a couple of times. Once, when she was in Deep Rover, someone had opened the sea water intake valve by mistake and water poured into the submersible; she was quickly rescued. Edie was rattled but “got back on the horse”.

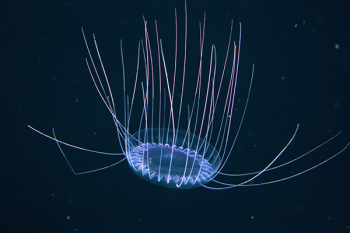

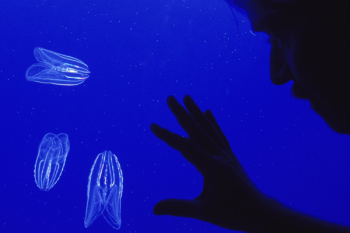

For decades the focus of Edie’s research has been the light in the deep sea made by creatures —bioluminescence. This phenomenon is used by animals to communicate, find prey and avoid predation in the dark, bioluminescence is extremely common in the deep sea. Even the marine snow (tiny flakes of animal poop, decaying animals and organic detritus that sustains most life in the deep sea) that falls from surface waters to the bottom bioluminescence. When you shine a light out the window of a submersible while exploring the deep sea, marine snow glows. If you flash a strobe it becomes a starry night: everything lights up and then fades out.

Scientists don’t know much about the bacteria in marine snow. Fecal pellets (poop) glow and scientists hypothesize that the bacteria in the fecal pellets glow to attract predators, allowing the bacteria to remain in the open ocean instead of sinking to the depths.

Edie developed an “electronic jellyfish” that imitates the “burglar alarm” of the jelly Atolla. First Edie wanted to see in the dark with no lights on the submersible using a camera system she developed call the “Eye-In-the-Sea” that uses a red light that deep sea animals can’t see.

After only 86 seconds the camera recorded a six-foot long squid coming in. It turned out to be an animal from a previously unknown family of large squid. Since that expedition The Eye-In-the-Sea and its predecessor, the Medusa have been deployed in many places around the world. In 2012 when the Medusa was deployed off Japan it captured the first video ever recorded of a giant squid in its natural habitat . It was an incredible thrill for Edie and her fellow scientists.

Ocean Research and Conservation Association

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, where Edie worked for sixteen years, was losing its submersibles. Around the same time two reports on the state of the oceans from the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy and the Pew Oceans Commission were released detailing threats to the oceans. This was a wake-up call for Edie and she founded the Ocean Research & Conservation Association (ORCA) in 2005 “to lead the effort of translating complex scientific issues into technological solutions, and to foster greater understanding of ocean life as a means to better, more informed stewardship.”

2006 Edie received a MacArthur Fellowship, which then sustained ORCA. The ocean reports called for advanced monitoring to protect and restore ecosystems. Edie had spent so much time with engineers that she knew she could help. ORCA became the first technology-based marine conservation organization in this country. Most pollution in aquatic ecosystems comes from the land, so Edie and her team decided to focus on the 156 mile-long Indian River Lagoon—their backyard. The lagoon was once healthy and full of life but it had become very polluted. Anything developed there to bring the ecosystem back to health could be useful elsewhere.

To monitor the Indian River Lagoon, ORCA developed KILROY: low-cost, state-of-the-art monitors that continuously measure water “speed, direction, temperature, salinity, depth, turbidity and prevalence of key micro-organisms” streaming the data.

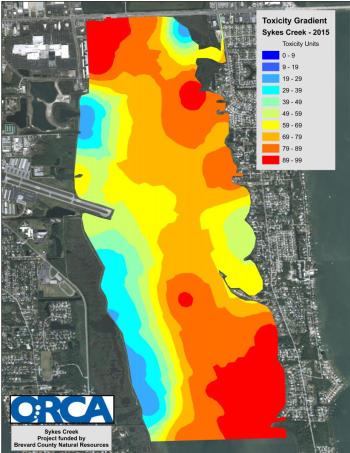

Where is the pollution in the lagoon coming from? The team has been seeking the most toxic areas and this is where Edie’s expertise in bioluminescence comes in. It turns out that anything that dims light is toxic. ORCA also has the Kilroy Academy for teachers that provides hands-on activities and lesson plans on how to access and analyze the real-time data from the Kilroy monitoring systems in the Indian River Lagoon.

Citizen Science

ORCA has a Center in Vero Beach where hundreds of students and community members can get involved in their projects. There are five projects now: pollution

mapping, living shorelines (growing plants to replace bulkheads and monitoring the sites over time), harvesting oysters in cages to test for pollutants, A Day In the Life of the Indian River Lagoon, and fish monitoring. Citizen Scientists are also tracking how toxins are getting into the food web.

They all receive rigorous training. Some go fishing and then test the fish for microcystin, the most common toxin in the blue-green algae blooms that can choke parts of the lagoon. That microcystin from toxic algae blooms can cause liver cancer. Some members of the subsistence fishing community are exposed. ORCA is working with the local medical community to inform them of the dangers.

The Great Blue Marble

Edie lives and now works on the Lagoon, with manatees coming up to her dock, and still conducts deep sea research. The deep sea is the largest habitat on the planet; earth is an ocean planet. The machinery of life depends on the deep sea and there’s still so much we don’t understand.

There are endless questions scientists are asking, like how the deep sea figures into the carbon cycle and the impact of ocean acidification on all ocean life. In June 2021, Edie heads off to the Azores with a new bioluminescence camera system. It's a smaller version of the Eye in the Sea and Electronic Jelly. Edie’s skills have opened many doors for her. Her advice to future scientists “take a variety of courses, learn skills so that you become indispensable and then you have a foot in the door to take you on a career path you might never have predicted”.