We all love a good tuna fish sandwich, or a yummy tuna sushi roll on occasion, right? But, did you ever think about the other vulnerable creatures unintentionally caught along with that tuna? Fortunately, Melissa Cronin does.

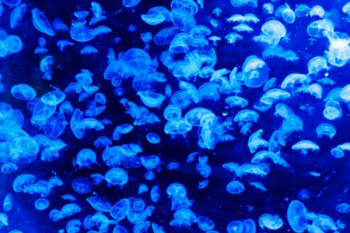

Every year we lose more than 13,000 manta and devil rays (genus Mobula) to small and industrial fishing vessels and nets. Being so large (sometimes as wide as a giraffe is tall), slippery and slow moving, it’s easy to see how they can be caught in a huge tuna fishing net. Manta rays are threatened, with reef manta rays currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’ and giant manta rays as ‘Endangered’.

Melissa and her colleagues have set out to identify and track the species in order to more safely protect them from industrial fishing.

Background

Melissa is a Post Doctoral Fellow at Duke University and works in partnership with Global Fishing Watch and Conservation International. She received her Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at UC Santa Cruz. Her research lies at the intersection of conservation and fisheries science. She is currently working on a project to understand the conservation and food security implications of large and small-scale fisheries interactions.

When asked about what influenced her aptitude for science she replied, “I don’t have an aptitude for science. My mother would laugh and tell you how I never did well in math. What I am good at is problem solving and communicating. I have always enjoyed making science accessible to everyone.”

Protecting Rays

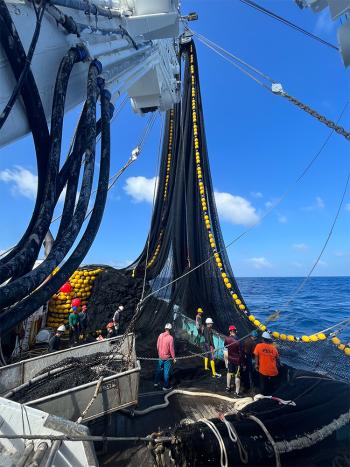

Today, Melissa’s research tracks fisheries bycatch patterns focusing particularly on mobulid (manta and devil ray) populations in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. She employs multiple approaches to describe this bycatch, including genetic analyses using tissue samples and spatial analyses of bycatch ‘hotspots’ based on extensive data obtained from the tuna purse-seine fishery. Melissa’s research estimates mobula population size in order to establish conservation goals and evaluate persistence.

“The real problem is the large rays,” says Melissa after spending six weeks on a purse seiner in the Pacific Ocean as part of a project at studying mobulid populations, bycatch rates and handling techniques. “They are very, very slippery. It’s like holding onto a slippery bar of soap. And they are the weight of a Honda Civic.”

The Importance of Protecting Rays

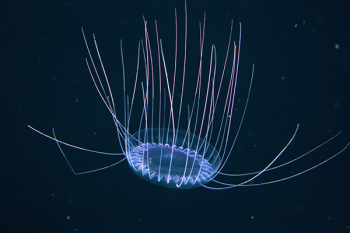

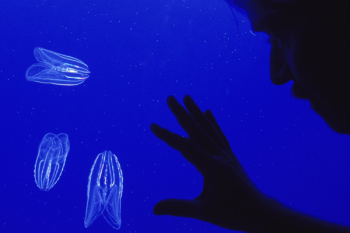

With the biggest brain-to-size ratio of any fish, these non-stinging gentle giants are a key species for reef health. Some rays travel between the deep ocean and coral reefs. The waste they accumulate while feeding on zooplankton acts as a fertilizer on the reef. The species also control plankton abundance and diversity and acts as an important connection between the deep sea and shallow ocean.

“As slow breeders Mobulids are exceptionally vulnerable. They are a large size at birth, with one of the lowest fecundity rates of all fishes, producing only one pup every 1-3 years,” says Melissa.

Taking on BIG TOPICS

No topic is too big or controversial for Melissa. “I had a wonderful mentor at NYU who taught me the importance of becoming exact and thorough in methodology. Solid problem-solving methodology is more likely to present irrefutable results and outcomes. This is what I love about the science process.”

In her former capacity as a journalist, Melissa has tackled topics like wildlife crimes, climate change, and politics. But it’s her work in preventing sexual harassment and assault in field sciences that recently grabbed my attention. Having just read The Exceptions book review in the NYTimes, I’ve become increasingly impressed by the women in science who (maybe reluctantly) became feminists in male dominated science fields.

Melissa is by no means ‘reluctant’ when addressing the real issue of equity in STEM. Collaborating with Dr. Erika Zavaleta and Dr. Roxanne Beltran, Melissa helped found the Building a Better Fieldwork Future (BBFF) Program at UC Santa Cruz. Dozens of men and women have already participated in the “interactive 90-minute training that identifies the unique risks posed by fieldwork, and offers a suite of evidence-based tools for field researchers, instructors, and students to prevent, intervene in, and respond to sexual harassment and assault.” It is now being replicated and incorporated into the science curriculum in several other universities.

Clearly Melissa is a champion of protecting all vulnerable species, human and otherwise.