Seven kinds of sea turtles swim tropical and subtropical oceans today, only coming to shore to lay eggs. Females make long migrations to the beaches where they were born (See Blog).

These are ancient creatures that have been around since the time of the dinosaurs. Scientists have found fossils of marine turtles from 120 million years ago.

Types of turtles

Although our Featured Creature is a Leatherback, we wanted to introduce the other six kinds of turtles.

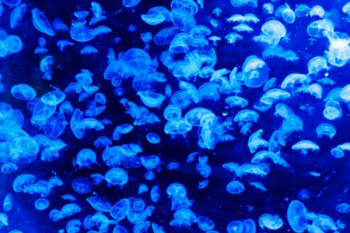

Greens: the largest of the species. They range coastal waters, bays, estuaries, and inlets worldwide, feeding on seagrasses, algae, mangrove leaves and shoots, and jellyfish.

Hawksbills: found in the world’s tropical and subtropical oceans in rocky zones, coral reefs and mangrove estuaries. On coral reefs they feed on corals, sponges, sea anemones, and other invertebrates.

Loggerheads: found worldwide. They are the most abundant sea turtle nesting in the United States. Juveniles and adult loggerheads inhabit coastal waters and eat mostly bottom-dwelling invertebrates including molluscs, crustaceans and horseshoe crabs.

Kemp’s Ridleys: the smallest and most critically endangered sea turtle. They occur in nearshore waters along the Gulf of Mexico coast from Florida to the Yucatan Peninsula, and as far north as Nova Scotia. They eat primarily crabs, but also fish, sea jellies, and molluscs.

Olive Ridleys: found throughout the world primarily in the tropical regions of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans. They mainly inhabit the open ocean, feeding on algae, crustaceans, tunicates, and molluscs. Both Kemp and Olive Ridleys come ashore to nest and lay their eggs on the beach all at the same time. This mass nesting event is known as an arribada, meaning “arrival by sea.”

Flatbacks: have a very limited distribution, from northern Australia to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, and only breed in Australia. They eat mostly benthic invertebrates like crabs, other crustaceans, and molluscs.

Leatherbacks

Leatherbacks inhabit the waters off every continent except for the Arctic and Antarctic. They dive deeper than any other marine reptile—below 1,000 meters (3,280 feet)— where the water is very cold and exerts extreme pressures. So how do they survive in this extreme environment? Believe it or not, their leathery shell helps them survive the high pressures of the deep. Because the shell is flexible, during a deep dive it can compress and not crack when squeezed under high pressure. In addition, the shell absorbs nitrogen which can be dangerous at high pressures.

Like other reptiles, leatherbacks are cold blooded. To tolerate the cold ocean temperatures, these turtles have adaptations to help them keep warm, including insulating fat and countercurrent heat exchange. This means that the body “…runs warm blood from their inner bodies out to their extremities next to the cold blood running back inwards. The two blood temperatures participate in heat exchange and, therefore, the cold blood is warmed before re-entering the body core.

Migration

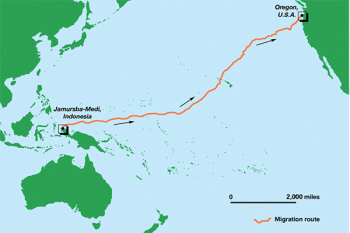

This map illustrates the migration of one female leatherback turtle, after nesting in Jamursba Medi, Papua, Indonesia, to foraging grounds off the coast of Oregon, United States— a distance of 20,558 kilometers (12,774 miles). © Stephen Nash / Conservation International.

In the Atlantic

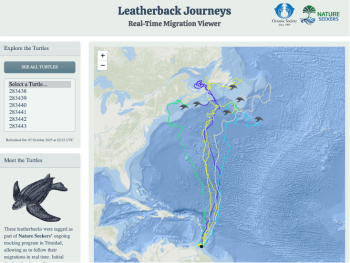

Although they nest in tropical regions, leatherbacks migrate long distances to feed in the prey-rich open ocean and along continental shelves. Scientists have tagged hundreds of individual turtles to follow their migration routes and learn about their feeding behavior. For example, West Pacific leatherbacks can make a 7,000-mile migratory journey within a 10 to 12-month period (see map).

When the females are ready to lay eggs, they head back to the place where they themselves hatched, often to the exact same beach. This requires excellent navigational skills. The maps that scientists construct based on tag data show that turtles can consistently travel south even through the currents of the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. This strongly suggests they can sense the earth’s magnetic field in order to keep heading south.

Is this also true of the tiny hatchlings as they head out to the open ocean from the beaches where they hatched? A recent study on loggerhead hatchlings showed that the hatchlings use a touch-based magnetic sense, meaning they feel the magnetism, to know where they are on their map. They are born with this sense.

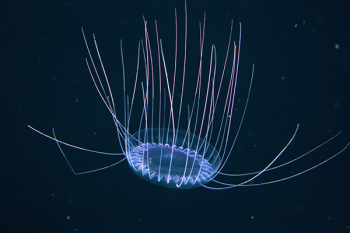

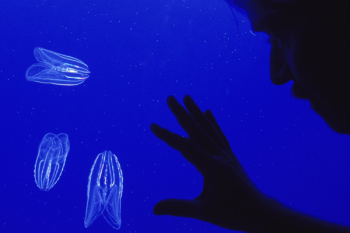

On their feeding journeys, leatherbacks feed on jellyfish, salps, siphonophores, pyrosomes, and other soft-bodied invertebrates. Knowing migratory routes can help conserve populations if governments set aside protected areas.