Curiosity Leads Karen Along a Career of Science and Adventure

Being from Michigan, Karen was familiar with large bodies of water. But she knew about the wonders of aquatic life through her dad who was a scuba diver. In college, Karen taught biology and art in Micronesia where she dived every chance she got and was completely astounded by the shapes, sizes and colors of all she saw on the coral reefs. There were animals she couldn’t identify at all, like sea cucumbers. She wondered how animals got to be where they are, what they ate, how did they avoid getting eaten, and how do they reproduce? So many questions set Karen on her career path.

After her experience on coral reefs, Karen chose to do a Master’s at Western Washington University to learn as many invertebrates as possible. She interned at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) where she was offered a position as a taxonomist, a great way to learn marine invertebrates. For her PhD at UC Berkeley she worked with Bruce Robison at MBARI where she focused on midwater ecology, a largely unexplored realm filled with mysterious and strange-looking animals, including polychaete worms.

Psyched About Polychaetas

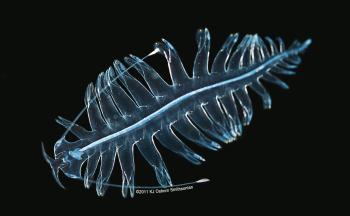

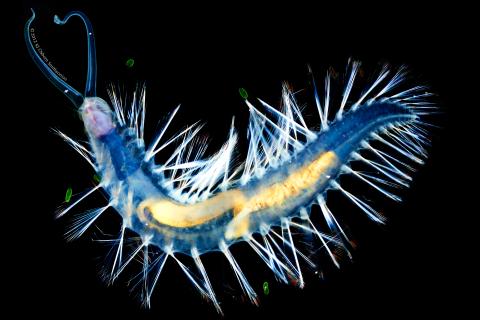

Karen is so enthusiastic about polychaete worms (polychaete translates to “many bristles”) that she launched International Polychaete Day. There are five different polychaete worm families found only in the midwater and they’re all a little odd, which intrigues Karen. These midwater worms are gelatinous, like so many animals in the midwater. How they evolved and how they survive is yet to be discovered for so many of them.

Researchers don’t know how gossamer worms (Tomopterids) are related to the others in the midwater. But Poeobius and Flota are examples of a midwater species known to have evolved from benthic-dwellers. These are just a few examples of midwater polychaete.

Curating AND Researching Annelids at the Smithsonian

As a Curator of Invertebrates at the Smithsonian, Karen oversees the collections for nine different groups including annelids, crustaceans and acorn worms (hemichordates). Though she is responsible for the collections, doing collecting, and promoting these groups, most of Karen’s job is research.

Heading to the Vast Midwater

Karen is very excited that she just received an Ocean Shot grant to explore the vast midwater and “discover new open ocean species and their functions.” The team will explore biodiversity in midwater by collecting and imaging animals in many regions of the ocean. They will then generate reference genetic sequences for midwater animals so that studies of environmental DNA can include open ocean animals. E-DNA is like nature’s fingerprint, and scientists are working to make it easier to see ‘who’ is in our ocean, where they go and how many of them there are just by sampling the water that they swim and drift through.

Discovering the Undiscovered

So much of the ocean is unexplored and this grant will open new areas for discovery of more midwater animals. Scientists will be able to answer basic questions like what structures the habitat? They don’t know why animals want to be where they are. Is it food, temperature or oxygen? What are the depth and geographic distribution of specific species? The grant will also analyze MBARI’s midwater time series to look at patchiness of species to answer the question: what’s driving distribution of midwater animals.

Climate and Weird Animals

Karen wants to “look at weird animals and figure out how they work.” She’s also wants to know how they function in their community and how their interactions effect carbon flux. There are billions of animals in the ocean that mediate the carbon cycle. They are either releasing carbon in the shallows or transporting it down deep. If we don’t grasp what’s going on in the deep sea, we can’t know how climate change is impacting the animals and their roles in carbon transport.